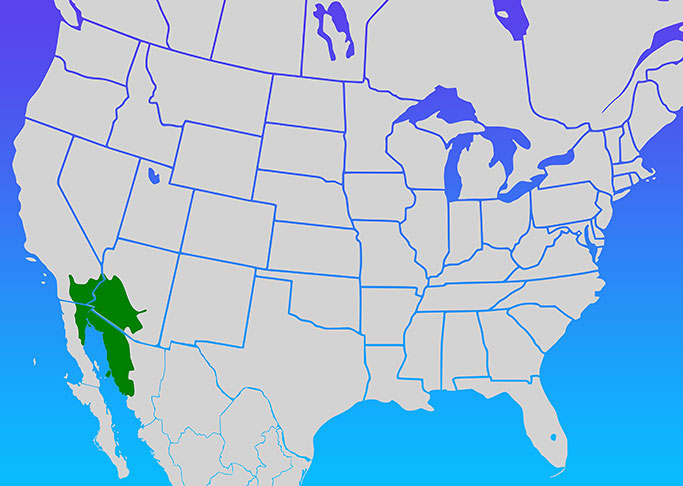

In early March 2021, I lgot off the plane in Phoenix and began my Arizona vacation by heading up toward the Grand Canyon. I knew I was in that desert environment so prominently romanticized in Western films due to the mighty Saguaro cacti I could see in every direction. If you see a wild Saguaro, you can be certain you are in the Sonoran. This 100,000 square mile desert in Arizona, Sonora Mexico, and a corner of California is the only place this cactus grows.

Cephas, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

By Joe Parks from Berkeley, CA - Saguaro National Park, CC BY 2.0

A Saguaro is hard to miss. They average 10-52 feet high with the tallest on record being 78 feet. When fully hydrated they can weigh between 3200 and 4800 pounds. These dimensions are reached over its 150-200 year lifespan. They have 3 inch spines, and had I been there in April, I may have seen its waxy white flower bloom. The root system typically fans out as far as the cactus is tall, about 3 to 6 inches underground with a 3 inch tap root.

SonoranDesertNPS from Tucson, Arizona, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Murray Foubister, CC BY-SA 2.0

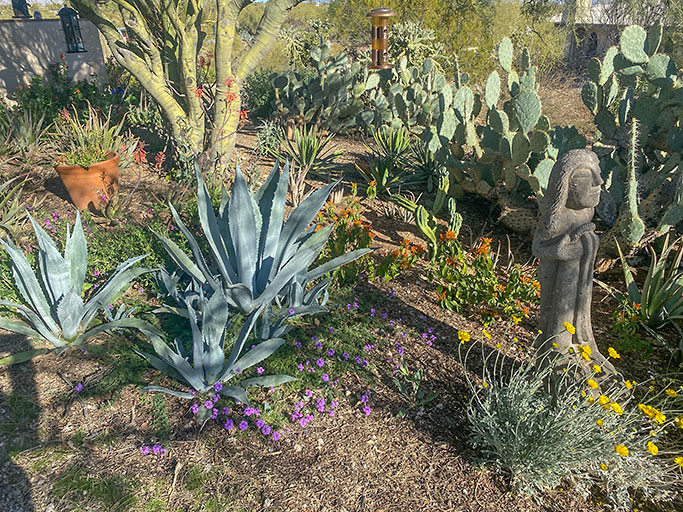

If you live in Arizona, but don't have a Saguaro on your property, you can have one planted. The best time is fall after the monsoon season. Plants under 5' can be purchased and planted by your average homeowner. Larger specimens require heavy equipment including cranes and backhoes. As much of the root system as possible must be preserved and the cactus must be planted in the same orientation in regards to the sun as it was where it was taken from. Only authorized companies are allowed to harvest Saguaro from landowners willing to sell them. Cacti with arms are more expensive than ‘spears’. Armless spears cost about $75-$125 a foot. A one-armed 75-90 year old specimen can go for $1500-$2300 installed. A large transplant cannot be deemed successful until an entire year has passed. I would hate to be the person who paid $2300 for a dead cactus, which does not include removal. When planting young Saguaro (sounds like a safer bet, but not nearly as impressive), make sure to give them a shade providing ‘nurse’ plant like the Palo Verde to give them a break from the unrelenting sun. If you don’t live in Arizona or Mexico, small plants can be grown indoors provided they have plenty of sun.

Saguaro with nurse tree - Katja Schulz from Washington, D. C., USA, CC BY 2.0

If I lived in southwest Arizona I think I would just go visit them at their home instead of kidnapping them and forcing them to live at mine, since they are plentiful inside and outside of urban areas. Or, I could just buy a piece of property that already has some.

SonoranDesertNPS from Tucson, Arizona, CC BY 2.0

So, remember...If you are lost and see Saguaros, relax. You are in the Sonoran desert and have narrowed down your location to an area about 100,000 square miles, and you are most likely in Arizona or Mexico. Technically no longer lost, at least on a global scale.

© John Mollon

© John Mollon

© John Mollon